Humans possess 46 chromosomes arranged in 23 pairs, making this one of the most fundamental facts about our genetic makeup. Each chromosome contains thousands of genes that determine everything from eye colour to height, creating the blueprint for human development and function. These threadlike structures reside within the nucleus of nearly every cell in our body, carrying vital genetic information from one generation to the next. While this standard number remains consistent across most people, certain genetic conditions can result in different chromosome counts, leading to various developmental and health considerations.

Human Chromosome Structure and Organisation

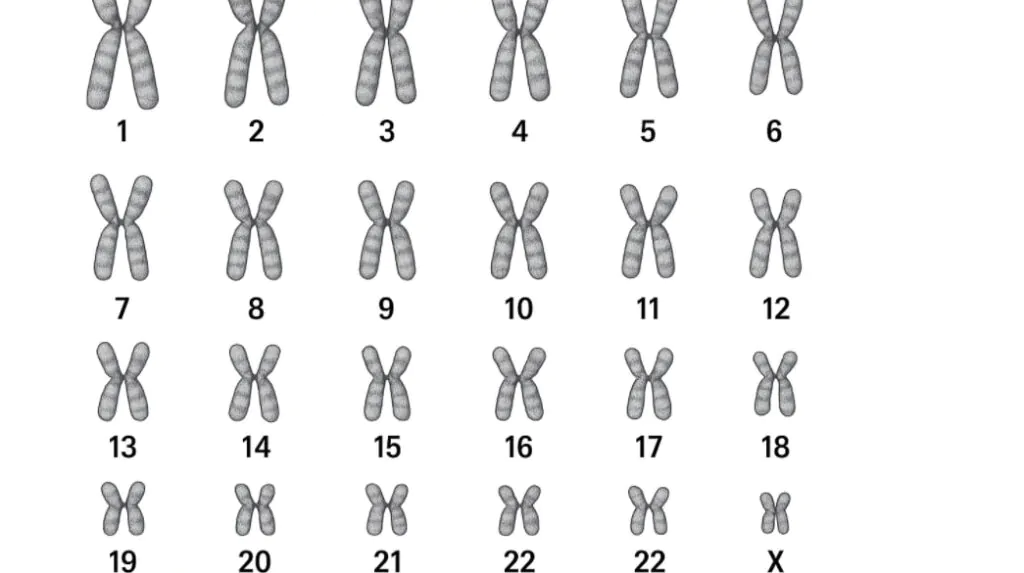

Each human cell contains chromosomes organised into distinct pairs, with one chromosome from each pair inherited from each biological parent. Twenty-two of these pairs, called autosomes, appear identical in both males and females, controlling most bodily functions and characteristics.

The twenty-third pair consists of sex chromosomes, which determine biological sex and differ between males and females. Females typically possess two X chromosomes (XX), while males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY).

This arrangement creates what scientists call a karyotype, representing the complete set of chromosomes in an organism. The human karyotype of 46 chromosomes provides the genetic foundation for normal development and cellular function.

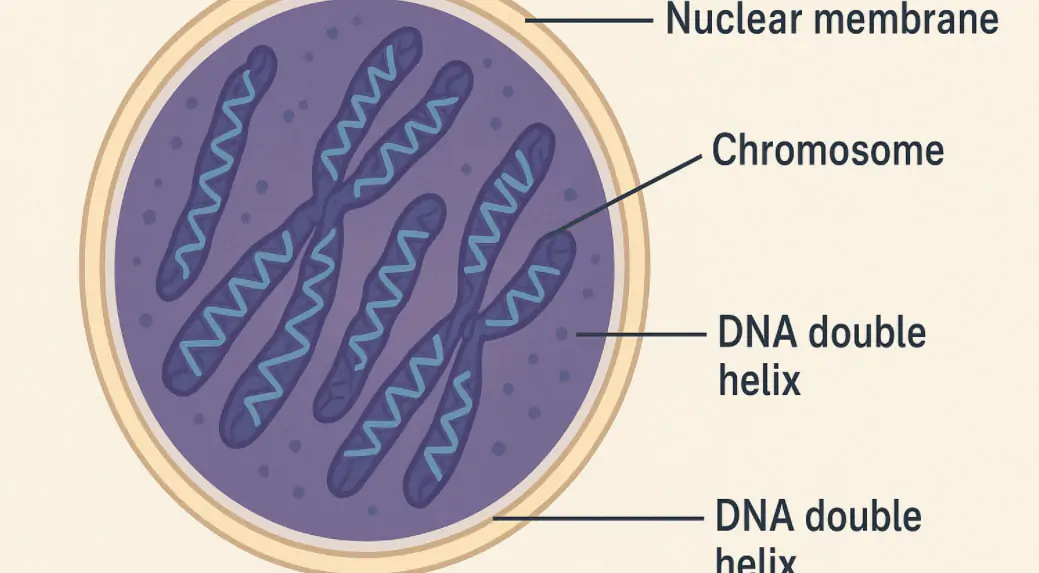

Furthermore, chromosomes consist of tightly wound DNA molecules combined with proteins, creating structures visible under powerful microscopes during cell division. This packaging allows enormous amounts of genetic information to fit within the microscopic cell nucleus.

Common Numerical Variations

| Condition | Chromosome change | Key features (brief) |

|---|---|---|

| Trisomy 21 Down syndrome | Extra chromosome 21 | Characteristic facial features, variable learning disability, certain heart and thyroid risks |

| Trisomy 18 Edwards syndrome | Extra chromosome 18 | Severe developmental issues, high infant mortality |

| Trisomy 13 Patau syndrome | Extra chromosome 13 | Severe organ and facial differences |

| Turner syndrome | Single X only (45 X) | Short stature, ovarian insufficiency, some heart and vascular differences |

| Klinefelter syndrome | XXY (47) | Tall stature, testicular insufficiency, some learning differences |

| Triple X syndrome | XXX (47) | Often mild or no obvious physical signs |

| XYY syndrome | XYY (47) | Often normal phenotype with possible taller stature |

NHS services offer prenatal screening pathways and diagnostic tests for some of these conditions. Not every variation produces clear symptoms and many people with sex chromosome variations lead typical lives with tailored medical support.

23 Pairs of Chromosomes Humans Inherit

Understanding how humans acquire their chromosome complement involves recognising the contribution from each parent during reproduction. Reproductive cells, called gametes, contain only 23 chromosomes each rather than the full complement of 46.

When fertilisation occurs, the egg contributes 23 chromosomes while the sperm provides another 23, restoring the complete set of 46 chromosomes in the developing embryo. This process ensures genetic diversity while maintaining the species-specific chromosome number.

Each chromosome pair contains similar genes in the same locations, though the specific versions of these genes may differ between the maternal and paternal chromosomes. These variations contribute to individual differences in appearance, health, and other characteristics.

Additionally, this pairing system allows for genetic repair mechanisms, as cells can often compensate for damaged genes by using the corresponding gene on the partner chromosome.

Sex Chromosomes and Gender Determination

Sex chromosomes play a unique role in human genetics, differing from the other 22 pairs in both structure and function. The X chromosome contains approximately 1,100 genes, while the much smaller Y chromosome carries only about 80 genes.

Males inherit their X chromosome from their mother and their Y chromosome from their father, making paternal genetics responsible for determining biological sex. Females receive X chromosomes from both parents, creating different patterns of gene expression.

This system creates interesting genetic implications, particularly regarding X-linked genetic conditions. Since males have only one X chromosome, they express all genes on this chromosome, while females may have different versions of the same gene on each X chromosome.

The presence or absence of the Y chromosome triggers different developmental pathways during embryonic growth, leading to male or female biological characteristics respectively.

Chromosome Disorders and Variations

While most humans have 46 chromosomes, certain genetic conditions result from different chromosome numbers or structural abnormalities. Down syndrome represents the most common chromosome disorder, caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21, resulting in 47 total chromosomes.

This condition, also known as trisomy 21, affects approximately 1 in 800 live births and demonstrates how chromosome number variations impact human development. People with Down syndrome may experience intellectual disabilities alongside characteristic physical features. Turner syndrome affects females who have only one X chromosome instead of two, resulting in 45 total chromosomes. Conversely, Klinefelter syndrome occurs in males with an extra X chromosome, creating an XXY pattern with 47 chromosomes.

These conditions highlight the importance of proper chromosome distribution during cell division and reproduction. Most chromosome abnormalities arise during the formation of reproductive cells, though some may occur during early embryonic development.

Chromosome Function and Gene Expression

Chromosomes serve as vehicles for genetic information, with each chromosome containing hundreds to thousands of genes arranged in specific sequences. These genes provide instructions for producing proteins essential for cellular function and human development.

Gene expression patterns vary between different chromosomes and different regions within chromosomes. Some chromosomal regions remain tightly packed and relatively inactive, while others stay accessible for regular gene expression. The relationship between chromosomes and health extends beyond simple gene number, involving complex interactions between different genetic regions. Changes in chromosome structure, even without altering gene number, can significantly impact human health and development.

Modern genetic research continues revealing new connections between chromosome organisation and various health conditions, improving our ability to diagnose and treat genetic disorders.

Etymology and Scientific Discovery

The term “chromosome” derives from Greek words meaning “coloured body,” reflecting early scientists’ observations of these structures when stained with dyes for microscopic examination. German anatomist Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer coined this term in 1888, though the structures themselves were first observed decades earlier. Scientists initially struggled to determine the exact number of human chromosomes, with early estimates ranging from 24 to 48 pairs. The correct count of 23 pairs wasn’t definitively established until 1956, when researchers Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan used improved techniques to achieve accurate chromosome counting.

This relatively recent discovery demonstrates how technological advances continue improving our knowledge of human genetics. Modern chromosome analysis techniques now allow scientists to examine not just chromosome number but also detailed structural variations. The development of karyotyping techniques revolutionised genetic medicine, enabling doctors to diagnose chromosome disorders and provide genetic counselling to families.

Modern Chromosome Research and Applications

Contemporary chromosome research extends far beyond simply counting chromosomes, investigating how chromosome structure influences gene expression and human health. Scientists now examine chromosome territories within cell nuclei, studying how chromosome positioning affects cellular function. Advances in genetic sequencing allow researchers to map exact gene locations on each chromosome, creating detailed genetic maps for medical and research applications. This information helps identify disease-causing genetic variations and develop targeted treatments.

Chromosome research also contributes to personalised medicine approaches, where genetic information guides treatment decisions. Like how understanding proper nutrition supports physical health, genetic knowledge supports medical decision-making. Additionally, chromosome studies inform evolutionary biology, helping scientists trace human ancestry and relationships with other species through chromosome comparisons.

Clinical Significance and Testing

Medical professionals routinely use chromosome analysis for diagnosing genetic conditions, particularly during pregnancy and for individuals with developmental delays. Prenatal testing can detect major chromosome abnormalities, allowing families to make informed decisions about pregnancy management.

Chromosome testing, called karyotyping, involves examining chromosomes under microscopes to count them and identify structural abnormalities. More advanced techniques like chromosomal microarray analysis can detect smaller genetic changes not visible with traditional methods. These diagnostic tools prove essential for genetic counselling, helping families understand inheritance patterns and recurrence risks for genetic conditions. Early diagnosis often enables interventions that improve outcomes for individuals with chromosome disorders.

Furthermore, chromosome research contributes to cancer treatment, as many cancers involve specific chromosome changes that can guide therapy selection and prognosis assessment.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all humans have exactly 46 chromosomes?

Most humans have 46 chromosomes, but some people have different numbers due to genetic conditions. Down syndrome involves 47 chromosomes, while Turner syndrome typically involves 45 chromosomes. These variations occur in a small percentage of the population.

Why do humans have 23 pairs rather than a different number?

The number 23 represents the result of evolutionary processes over millions of years. Different species have different chromosome numbers, suggesting this arrangement developed specifically for human genetics and reproduction. Scientists believe this number provides optimal genetic stability and diversity.

Can someone survive with missing chromosomes?

Survival depends on which chromosomes are affected. Missing entire autosomes (chromosomes 1-22) typically prevents survival, while sex chromosome variations like Turner syndrome (missing one X) can be compatible with life, though they may cause health challenges.

How do doctors count chromosomes?

Medical professionals use a technique called karyotyping, which involves photographing chromosomes under powerful microscopes during cell division when they become visible. Laboratory technicians then arrange and count the chromosomes systematically.

Are chromosome numbers the same in all body cells?

Nearly all body cells contain 46 chromosomes, except reproductive cells (sperm and eggs) which have 23 chromosomes each. Some specialised cells may have variations, but the vast majority maintain the standard 46-chromosome complement.

Can chromosome numbers change during a person’s lifetime?

Individual cells may occasionally gain or lose chromosomes through errors during cell division, but this doesn’t change the overall chromosome number throughout the body. These changes typically affect only small numbers of cells and may contribute to aging or cancer development.

References:

- MedlinePlus Genetics: How many chromosomes do people have?: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/basics/howmanychromosomes/

- National Human Genome Research Institute: Chromosome: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Chromosome

- CDC: Down Syndrome: https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/down-syndrome.html

Article Summary

Humans typically possess forty six chromosomes in twenty three pairs with one set from each parent. Gametes carry twenty three. Variations in number or structure can affect development and health though many sex chromosome differences produce mild or no symptoms. The term chromosome reflects Greek roots for colour and body, showing historical staining methods. Modern UK clinical practice uses both visual and sequencing techniques to assess number while patient centred support frames ethical considerations.